PRIS takeaways: How to successfully switch providers?

Switching payroll providers isn’t about cost alone. Our latest PRIS webinar reveals the real triggers, risks and readiness needed to make change succeed.

In our latest Payroll and Insight Series, Vickie Graham, Managing Director at Reward Strategy, and Simon Bunday, Director at LACE Partners, discussed how to successfully change providers and one theme surfaced repeatedly: organisations almost never wake up one morning and decide, lightly, to change payroll provider. What emerged instead was a picture of slow-building pressure-operational, regulatory and organisational-that eventually reaches a tipping point.

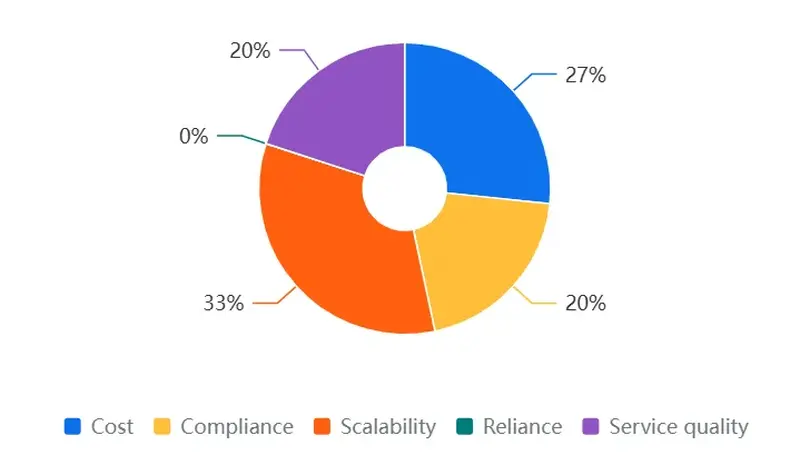

After a group poll questioning what the original reason participants chose their current provider was, Simon was clear that cost savings alone rarely justify such a disruptive move. Changing payroll demands time, internal effort and senior attention. In most cases, the business case only stacks up once multiple pain points converge; deteriorating service quality, rising error rates, audit concerns, organisational growth, and major internal transformation programmes all tend to overlap before serious questions are asked about whether the current provider is still fit for purpose.

Service pain hidden behind firefighting

One of the most striking insights from the discussion was how long payroll teams absorb operational pain before it becomes visible to the wider business. Missed SLAs, weak incident management, heavy rework after payroll runs and reliance on a small number of provider staff with critical knowledge were all cited as common triggers. Yet these issues are often masked by constant “firefighting” from payroll and HR teams determined to ensure people are still paid correctly and on time.

By the time senior stakeholders become aware-often through audit findings or compliance concerns-the underlying problems are already deeply embedded. At that point, payroll risk shifts from an internal inconvenience to a financial, regulatory or reputational issue that boards cannot ignore.

System failure or operating model failure?

A recurring question throughout the seminar was how organisations can tell whether the real problem lies with the payroll system itself or with how payroll is operated day to day. Simon suggested two practical tests:

First, dissatisfaction needs to be unpacked: is it about what the provider delivers, or what the technology can actually do? Slow responses, limited payroll expertise and poor quality assurance tend to signal service or operating-model issues. By contrast, rigid configuration, constrained data models and weak reporting usually point to genuine system limitations.

Second, organisations were urged to trace where errors originate. If mistakes are being introduced upstream-through HR data, time inputs, manual uploads or poorly designed workflows-the platform may not be the culprit at all. Several contributors warned that many organisations replace their payroll provider only to recreate the same problems because underlying processes and governance remain unchanged.

What “readiness” really looks like

Perhaps the most pragmatic part of the seminar was the discussion on readiness. Simon was explicit that being “ready” does not mean having a perfect payroll operation. It means having clarity.

In practice, this includes a shared understanding of how payroll actually operates today, evidence-based pain points rather than vague dissatisfaction, and a clear payroll strategy that sets direction and ambition. Just as importantly, readiness requires visible senior sponsorship and agreement on ownership across Payroll, HR and Finance.

The discussion noted how often key stakeholders are engaged too late. Line managers, operational users, works councils and even employees themselves are frequently treated as peripheral, despite payroll touching almost every part of the organisation. The seminar made a compelling case that excluding these voices early almost guarantees misalignment and rework later on.

Redefining what “good payroll” means

Another strong takeaway was the emphasis on defining success before any provider review begins. Paying people accurately and on time is non-negotiable, but it is not, on its own, a meaningful definition of success.

It was argued that good payroll should feel predictable and stable, with clear accountability, strong controls and minimal dependency on individual knowledge. It should enable wider business change, not constrain it. For employees and managers, success shows up as simplicity, reliability and trust-qualities that are difficult to retrofit if they are not designed into the operating model from the outset.

The risks organisations still underestimate

The same underestimated risks kept resurfacing. Data quality was chief among them. Organisations often assume historic data issues will be resolved during implementation, only to discover late-stage inconsistencies in job structures, pay elements and local exceptions that force compromises.

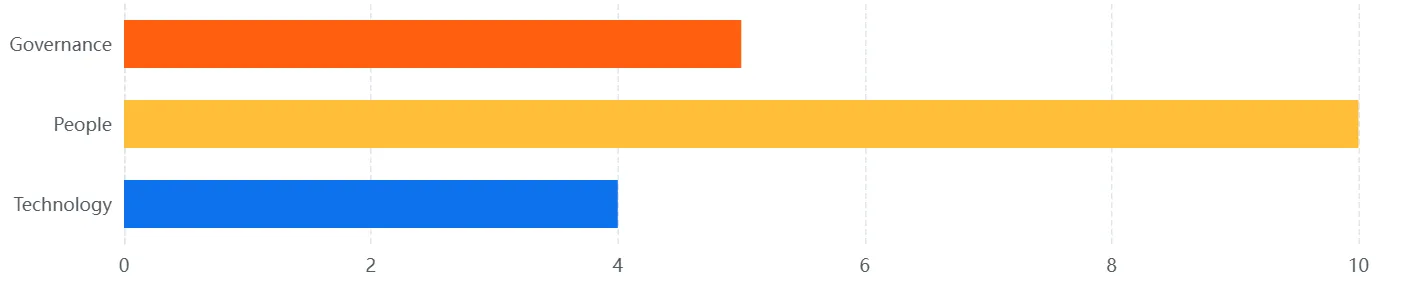

Change fatigue was another recurring concern. Payroll transformation rarely happens in isolation and often coincides with HR or finance programmes, stretching internal capacity and weakening engagement. Closely linked was the tendency to underestimate internal effort and over-rely on provider teams who lack deep organisational context, a view supported by the participants in a poll.

Finally, unclear boundaries between customer and provider responsibilities-particularly around data validation, exception handling and statutory reporting-were highlighted as a persistent source of friction and escalating cost.

Looking beyond cost and technology

The seminar closed with a reminder that payroll selection decisions succeed or fail well beyond spreadsheets and feature lists. Operating model, service delivery structure and cultural fit matter enormously in the long term. Payroll is not a one-off project but an ongoing partnership, with providers effectively becoming an extension of internal teams.

The importance of understanding how providers retain payroll expertise, how delivery teams are stabilised, and how feedback is used to improve service were stressed as key factors. When operating across borders, the challenge becomes even sharper. Global consistency brings governance and efficiency, but local payroll realities, legislation, language and practice, cannot be abstracted away.

The overriding message from the webinar was clear. Organisations that approach payroll change as a purely technical or commercial exercise are likely to be disappointed. Those that treat it as a strategic, operational and human endeavour stand a far better chance of delivering lasting improvement.

The Payroll and Insight Series continues to evolve to keep you up to date with thought-leading topics and insights. Click here to see our next session: Neurodiversity in payroll.

Lukas Montgomery

Lukas Montgomery